How white supremacists created pop country music

Banned Histories of Race in America

In last week’s Beyoncé and the theft of country music I wrote about the genre’s hidden Black history. For the sake of your inbox, I left out another important part of that history. But this week Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter hit No. 1 on the Billboard country charts, so…

You know that good-ol’-days game that self-victimizing bigots play about how “You could never get away with that these days”? I love that game because it’s so provably wrong that it’s very easy to win. The opposite is almost always true. For example, Kris Kristofferson’s first album Kristofferson hit the Top-10 Billboard Country charts in 1971 and it had two anti-cop songs on it. Do you think you could get away with that these days?

See what I mean?

One of those songs was “Best of All Possible Worlds”, in which Kristofferson explained in a 2005 interview, “They wouldn’t let me demo it the way that I wrote it. I wrote it as, ‘If that’s against the law, tell me why I never saw a man locked in that jail of yours that wasn’t either Black or poor as me.’ The wouldn’t let me say ‘Black.’ I changed it to ‘low-down poor,’ but I don’t sing it that way now; I sing ‘Black’ every time.” In every live version of the song I could find, he sings “Black”.

Can you imagine a song like that being on a Billboard Top 10 Country album these days? Now consider that the other anti-cop song on Kristofferson is “The Law is for Protection of the People” in which he likens the police harassing the homeless and hippies to the police that crucified Jesus. These days? Your imagination cannot comprehend.

So, what happened? How did pop-country go from a genre that sang in common sentiment to one that so often fulfills its stereotype of white supremacist anthems and fascist singalongs? Believe it or not, there is an actual answer and it begins with one of the most famously racist politicians this country has ever spat out: George Wallace.

If you’re not familiar, Wallace was a piece-of-shit Alabama governor who said desegregation, “will result in the races mixing socially, which… will bring about intermarriage of the races and eventually our [white] race will be deteriated [sic] to that of the mongrel complexity.” Wallace also famously attempted to physically stop Black students Vivian Malone and James Hood from entering the University of Alabama. President Kennedy had to federalize the Alabama National Guard to force Wallace aside. Like I said, piece of shit.

This piece of shit ran for president in 1968 and drew huge crowds by campaigning with country musicians. He reportedly told one of his aids that country music fans would elect him president. They did not. Instead, Richard Nixon found victory by playing to racists, out-Wallace-ing Wallace in the South with a plan called the Southern Strategy.

Enter: fellow racist and former Country Music Association (CMA) President Woodward Maurice “Tex” Ritter. Ritter loved Nixon so much that he volunteered to lead his own arm of the Southern Strategy. If Nixon would bring eyes to country music, Ritter would make Nixon look like a regular human man capable of enjoying things.

With Ritter’s vision of country music, Nixon could represent those fictional wholesome good ol’ days and not have to appear his actual bigoted, paranoid maniac self and so he started making a real big deal out of country music. And it worked. In 1969 the CMA Awards were televised for the very first time. Country music became more popular than ever as the market grew, guided by white supremacy. Nixon became the first president to visit the Grand Ole Opry. He declared October of 1970 the very first Country Music Month. His 1972 campaign song was the perfect bland, country corn-pop of the era.

The CMA awarded Nixon with a custom-made LP Thank You, Mr. President. It featured 15 songs with Ritter introducing each one in the most embarrassing, ass-kissing, boot-licking way possible. Ritter thanked Nixon for “paying homage” to the “working man” and a whole bunch of other shit that I’m cringing too hard to actually type out. But in these intros, Ritter also said that country music was the voice of Nixon’s “Silent Majority,” a dog whistle catchphrase translating to “polite racists”. The kind that picked Nixon over Wallace, for example.

Nixon also started inviting country music artists to perform at the White House. One was Roy Acuff, a former blackface performer who would come to be known for protesting Black musician Deford Bailey’s induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

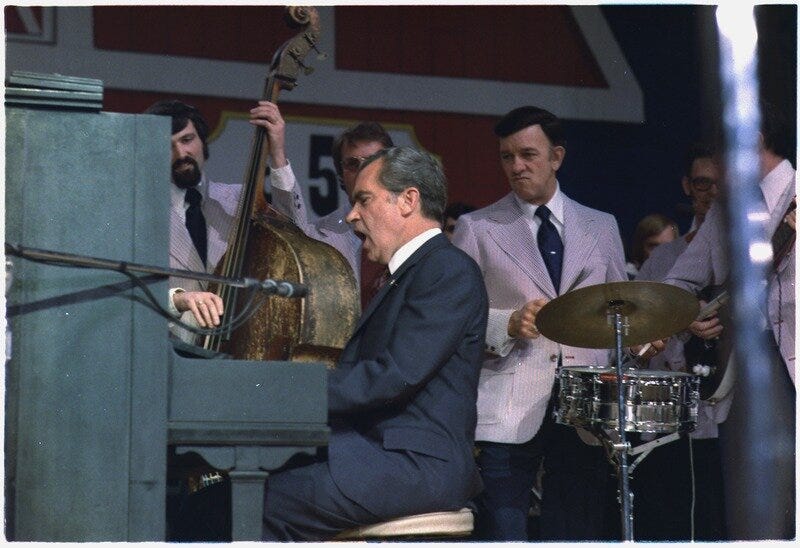

Another, however, was Johnny Cash, whose invitation Nixon immediately regretted. Nixon had asked Johnny to cover Guy Drake’s wildly racist song, “Welfare Cadillac”. Johnny refused, later referring to the song as “anti-Black” and instead performed his own anti-war protest songs, “What is Truth?” “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” and “The Man in Black”.

As we all know, Nixon eventually resigned in disgrace, and plenty of country singer/songwriters celebrated. John Denver had already released a five-second-long track of complete silence called “The Ballad of Richard Nixon”. Tom T. Hall released “Watergate Blues”. Even complete asshole David Allan Coe released “How High’s the Watergate, Martha?”

While Country Music itself continued to be—and still is—a place of common sentiment, the Country Music Industry and its market were set to follow the dipshit bigotry and plastic patriotism of Nixon’s Southern Strategy. In 2003, when The Chicks’ lead singer Natalie Maines said from stage that she was “ashamed” that George W. Bush was from Texas, corporate Country Music stations banned The Chicks and organized CD-burnings. Remember Jason Aldeen’s lynching hit “Try that in a Small Town”? Oliver Anthony’s weird, racist, QAnon chart-topper “Rich Men North of Richmond”? And you’ve probably noticed the little, tiny-minded whites hiding from Beyoncé.

The country as a whole also hasn’t managed to break from the Southern Strategy just yet. No Democrat in a presidential race has won the majority of the white vote since Lyndon Johnson, Nixon’s predecessor in 1964. Even Biden lost the white vote by 12 points in 2020. But in the spirit of not getting away with it these days, I’ve put together a playlist of many of the songs I mentioned here—not the racist or fascist ones—and a few others written in the common sentiment that somehow exist outside of “popular” country music.