This week the Supreme Court heard arguments in a case involving the homelessness crisis. Their decision should arrive in June, but don’t expect solutions. This particular case is about how unhoused people should be punished, not how a crisis should be solved. I’m sure a lot will be said about how complicated the whole issue is, but is it?

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development says it would cost $20 billion to solve this crisis. Did you know that the Pentagon has never passed an audit and that last year they couldn’t account for $1.9 TRILLION of their own assets? That’s more than the entire annual budget of the country and I don’t ever want to hear anyone say we can’t afford anything ever again.

So, if it’s not about having the money, what’s the complication? Why can’t we solve this problem? If you’ve read my posts before, I bet you have some idea. The answer, as usual, is in our history.

The first officially documented cases of homelessness in this country were in the 1640s, and that “official” record is a big part of the problem. It leaves out the 20 kidnapped Africans brought to the Virginia colonies in 1619 who were definitively homeless. It also leaves out any number of Indigenous peoples pushed from their homes before that. We define homelessness in our history along racial lines, even when not saying it out loud.

California, for example, had the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, signed into law in 1850 before California was even a state. This was a vagrancy law used to enslave indigenous peoples and enable the California Genocide, but “Protection of Indians”, though.

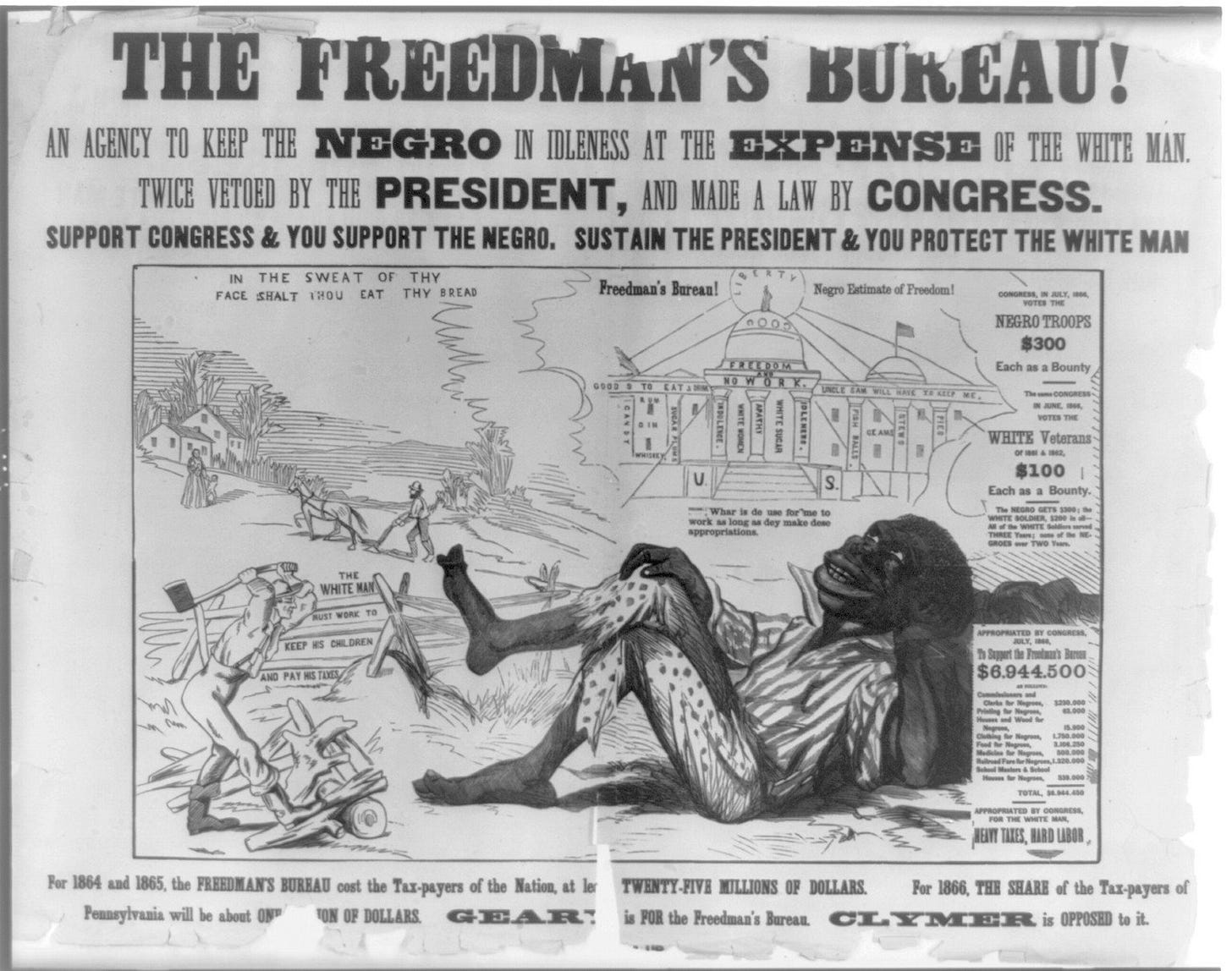

The Virginia Assembly passed what was called The Vagrancy Act in 1866, but its full title was the Act Providing for the Punishment of Vagrants. Its preamble read, “there hath lately been a great increase of idle and disorderly persons in some parts of this commonwealth.” That sentence doesn’t mention race. But, since there were suddenly a whole lot of free Black folks in Virginia and not a sudden influx of white people, it’s not difficult to figure out which “vagrants” the act was intended to punish. It should be no surprise to discover that vagrancy laws were a key part of the Black Codes and then Jim Crow laws used to criminalize Black American existence until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Officially, anyway.

Homelessness is criminalized to criminalize not being white. Rich whites have a tendency to sacrifice lower whites just so they can punish non-whites. Like in 1902, when Virginia re-wrote its constitution to include a poll tax and literacy test. The point was to eliminate the Black vote, which it did. They disenfranchised 90% of Black voters, but almost 50% of white voters, too. And I’m sure they thought it was worth it.

Sometimes the lower whites will voluntarily hurt themselves just to hurt non-whites. Like in the 1950s when white people started closing their own public pools to keep Black people from swimming in them. The Supreme Court even ruled on this in Palmer v. Thompson. The Court held that, “A city may choose not to operate desegregated facilities if its decision appears neutral on its face.”

That’s the quiet part out loud about the quiet part out loud. Just don’t openly admit to acting out of racism and it’ll all be fine. The brutal fact that Black people are only 13% of the US population, but 36% of the unhoused population can be blamed on the victim by default. That disproportionate statistic, by the way, can grow exponentially when the Black population is smaller. In my home state of Maine, we’re only 2% of the population, but more than 47% of the unhoused.

So, yeah. We could fix this crisis tomorrow, but like I’ve written about gun laws, drug policy, insurance, abortion, etc., without confronting its racist purpose, history and function, we can’t solve anything.

Anyway, this story from earlier in the week is about a millionaire who gave it all up and became homeless just to prove he could make it all back in a year. Spoiler alert: he didn’t and it’s pretty funny.

https://thebollard.com/2024/01/09/racisms-59/

https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/261

https://www.mainehousing.org/docs/default-source/housing-reports/2023-point-in-time.pdf

Thank you, Sam.